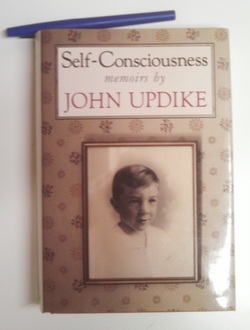

In November of 2001, back when I was a mere bookseller at the local bookstore, I was shelving in the U’s when I came across John Updike. It was a name I knew I knew, though I didn’t know why. I was 17, too naïve to know his prominence in the writing world; nevertheless, a sign directly above his books indicated that he would be reading in town the following week, and so, I decided to attend. The night of the reading, I listened intently as that old man with his shock of white hair read from Licks of Love, a book I’ve yet to read myself (much preferring the memory of Updike reading it to me). By reading’s end—even though I was floored by his talent—when I finally met the man face-to-face, all the 17-year-old me could muster were the regrettable words: “What was it like to be on The Simpsons?” As our hands clasped, it had suddenly occurred to me how I knew John Updike. He’d voiced himself in a recent episode, and as an avid watcher (and not yet an avid reader, regrettably), this had served as my introduction to the man. Long story short: Updike paused, mulled it over, and then remembered that yes, he had, in fact, been on The Simpsons, and that it was fine. A little context, Friend. I am no longer 17. In fact, I’m writing to you from the dining room table at 5:49a.m. on my 30th birthday. M.’s already one day past her due date, which means there’s at least some chance—if I’m lucky—I’ll be sharing my birthday cake for the rest of my life. Given these circumstances, I doubt it’ll surprise you to learn that when delving into Updike’s memoir Self-Consciousness earlier this week, I read it mostly for what might be gleaned from his attempts to balance family life alongside writing. Like this gem, describing his early years of fatherhood/writing: “In summer, though, what fullness of life, it seemed, to put in a few hours at the typewriter and then race downstairs…and leap into a station wagon or convertible containing my wife and a quartet of children, all of them plump and brown in their bathing suits!” It sounded like a good strategy to me: work followed by play. But what I’ve already learned—and likely what Updike learned—is that it’s far easier to break one’s work schedule than one’s play schedule, especially when the rest of your gang is honking the horn of the station wagon to hustle you out the door. And how can anyone in good conscious say no when loved ones try to liberate? How can one say, “Sorry perfect summer day (which I’ll never get again), and sorry family (which I'll also never get again), but I must further confine myself to a chair so that I can write feverishly and then delete most of what I write.” What kind of madness is that, Friend, and who would ever forgive such a trespass? Of course, Updike enumerates other perceived trespasses as well. In particular, he describes a revealing scene several years later—after his marriage had soured—when he learned that the dander from the family cats was the cause of his breathing problems. Updike writes that his wife “…saw, with me, that it was impossible to drown or give away Willy and Pansy, and that it was possible, at last that I go.” And so, John Updike left, beginning the irreversible splintering of his family. This is the outcome I’m trying to avoid, Friend, the one where the cats get priority. Given the choice, I’d much prefer leaping from the keys and hurling myself headlong into a waiting car en route to the beach. Would much prefer sand toys to ampersands, oceans to writing about oceans. When I feel pressure to write (and I often do), it’s always the result of the writer-in-me persuading the other-me than I’m writing for the family, that it's theirs, too. And I admit, dear Friend, that’s a lie I sometimes swallow. But then I remind myself: What good’s the writing without the subject? And what good are the words (even if they are good words) if written at such a high cost? In the final lines of Updike’s essay featuring the station wagon and the drive to the beach, the author mentions that he now lives (well, did live, may he rest in peace) within walking distance of a beach, and yet despite his proximity, he ventured there but three times a summer. He concludes: “Life suddenly seems too short to waste time lying in the sun.” As I sit at this dining room table at 6:29a.m., I'm just beginning to see flecks of sunlight dappling the trees. It's my cue to quit this letter. Write soon. Until then,

2 Comments

jack de bellis

5/25/2014 03:00:56 am

I'm compiling remembrances of Updike and thought this one was great. If you have anything to add, please write to me. I'm a prof. emeritus in English.

Reply

J. Pfeiffer

5/27/2014 04:42:35 am

How right. When the sun comes up, put away the work and live. Thanks.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorB.J. Hollars is a writer and a teacher. Archives

June 2014

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed