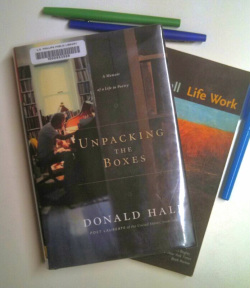

Dear Friend, I’ve spent the last few days cleaning out the storage room in the new house, and let me tell you, it’s been a transformative experience. Transformative for the room, sure, but transformative for me as well. I feel like I’ve finally found the guts of this place, and as I sit here—cross-legged on the old leather couch left behind by the previous owners—I’m just now getting a sense of the history of this structure. If the house is a body, then I am in its heart, ten-thousand wiry veins and pipes and electrical cords humming outward toward the extremities. Last night, as I was daydreaming down here, it was inconceivable to me that the copper pipe just above my head was the same copper pipe that ran water to the shower upstairs. It was a reminder, I suppose, that everything has its source, its starting place, its humble origin. Which is my less-than-subtle segue to this week’s read, Donald Hall’s Unpacking the Boxes. I hadn’t intended to read another Hall, but you know how it is—the mind goes where the mind wants to. I’d hardly finished Life Work before I knew I needed to read deeper into Hall’s life story. You and I are both young enough (and naïve enough) to believe there is something to be gleaned from autobiography, that cracking the code to the writing life might be as simple as imitating the lives and routines of our more successful predecessors. And so, every time Hall tells me he drinks black coffee and reads the Globe, I find myself wondering: Where the hell can I get a copy of the Globe? And when he writes about his leisurely dog walks around Eagle Pond, I think: Might some more centrally located pond work just as well? All of this is lunacy, of course, though my instinct toward imitation is the first step for many young writers. Yet what’s strange about this relationship (can I call it a relationship?) is that I have no intention to imitate Hall’s writing style, merely his lifestyle. During our senior year at college, I attempted a similar tact, though rather than seeking out black coffee and a subscription to the Globe, I followed in E.B. White’s footsteps. First, I considered adopting a dachshund like White’s hot-dog-impersonating, Fred. Next, I decided what I really needed was to purchase a remote farmhouse in Maine. When both of these larks fell through, I just went back to writing, hopeful that I might write my way into a position that would allow me to adopt the right dog, or at the very least, rent the right farmhouse. In Hall’s most recent memoir, he describes his own beginning: a young boy who at fourteen discovered he had a passion (and penchant) for poetry. The book tracks his growth from his Exeter years to his Harvard years to his years spent overseas. He writes about his poet friends (beers with Bly, spaghetti with O’Hara, bathing his baby while Adrienne Rich watched on), and perhaps there is a lesson here as well: always make friends with geniuses (though I suppose you and I will just have to make do with each other). Yet of the many autobiographical lessons Hall offers, I was most struck by an encounter he shared with his undergraduate professor, Archibald MacLeish. According to Hall, MacLeish accused the young writer of being “lazy,” which offended Hall, mainly because of the long hours he dedicated to his poems every day. Only later would Hall understand that MacLeish’s comment “…referred not to hours worked but to the ambition of my endeavor…” Hall added: “I began to grasp notions of scale.” This, of course, has long been our great debate. Do we write fast or do we write well? Do we allow our work to cool or must it always simmer? What are the proper proportions between reading and writing, and are we fools for dedicating too much time to either pursuit? Sometimes—as you’ve kindly pointed out in kinder terms—I find myself reaching for the low hanging fruit. But there’s a reason for it; namely, because the low hanging fruit is the fruit I know how to reach. This is not to say that I’m ashamed of my previous work or that the work came easily. Rather, it’s an acknowledgement that if that the conditions were right (if I had Hall’s newspaper, for instance, or White’s dog), maybe I could do better. I kid, of course, but only a little. The true conditions would include more time (always more time) and more energy (always more energy) and more genius (which we’ve already covered). And yet every time I sit down at the keys, I do what I can with what I have and hope I’m getting better. Rest assured, the fruit never seems low when I’m reaching for it, but I’ve also never consciously tried to reach higher. I fear that doing so might be my undoing, that raising the bar too high (or to continue the metaphor, “the branch”) would send me into a tailspin. After all, there’s less room to fall when the bar is low (not to mention that nobody ever starved eating low hanging fruit). All metaphors aside, what I’m talking about, really, is the fear of failure (and Lord knows you’ve heard me whine plenty about that). What’s nice about Unpacking the Boxes is that Hall devotes a bit of time to thinking about failure as well. Specifically, he writes about his two or three years lost in the poetic wilderness. How until that point, he’d been successful writing short-lined free verse, though after he “exhausted this vein,” he struggled to know where to go next. “…I felt frustrated,” he admitted, “and flailed about seeking a new speech.” I imagine finding one’s “new speech” is akin to recreating the wheel. Only in this version, you’re already quite familiar with the wheel you’ve got, and it’s always worked faithfully. What then, might provoke someone to let go of what works in search of what might not? Wouldn’t the risks be too great? Or perhaps Hall had found himself in a position where reinvention was possible, even imperative, to allow the work to continue. The work must always continue. That’s what Hall always seems to be getting at. Even in the face of his wife’s death, and his mother’s death, and his mother-in-law’s death, the writing continues. There’s a line from Robert Frost’s “A Servant to Servants” that I’ve been thinking about a lot lately: “…The best way out is always through.” Whether it’s grief, or writer’s block, or the curse of one’s continually humble origins, the best way out is through. And as I sit here on this abandoned couch in the heart of my house, I can’t help but wonder how anything ever gets through; how the tangle of wires and pipes always find its end point, even when no one’s watching. Write soon. I'd like to hear from you. Until then,

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorB.J. Hollars is a writer and a teacher. Archives

June 2014

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed