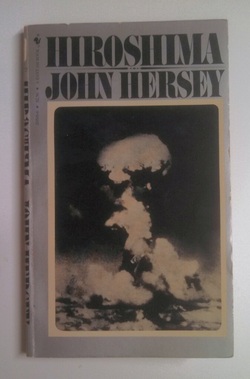

Dear Friend, This morning, as I wrapped up John Hersey’s Hiroshima, H. walked into my office, plucked my copy from my hands, and positioned himself on the rocking chair. “What’s that?” he asked, pointing to the cover. “That,” I said, “is an atomic bomb.” He considered this, studying the mushroom cloud before him, and at last concluded, “Oh, okay,” before abandoning the book for his toys. And that’s the story of how one little boy learned about another Little Boy. I admit, I’m always rather shocked, Friend, by the innocuousness of that bomb’s name. As if some PR man deep in the bowels of the Truman administration decided a name like “Little Boy” might soften the blow stateside. Might bolster Americans’ patriotic fervor by reminding us of what we were fighting for--Our little boys! Our little girls!—and help us forget the other boys and girls others fought for far away. After H. left the room, I found myself rereading the book from the start. Though this time, I focused on Hersey’s depiction of Hiroshima’s children, on the kids who—with the exception of time and place—were not unlike H. himself. Yes, my own son was born 68-years later and 6307 miles away, but that was all the distance between them. He just happened to be born on the right side of the bomb, by which I mean long after it had dropped. After wrapping up the book for a second time, I was disheartened to find children scattered throughout its pages. Like the story of Mrs. Kamai, just 20 at the time, who held tight to her dead infant daughter for four full days in the hopes her husband might return to say goodbye. And the story of the two young girls found shoulder-deep in the river, their bodies badly burned and absorbing salt water. There are so many other stories—of children who misplaced their mothers on their walks to theirs parks, and mothers who misplaced their children as well. Though of course, nobody “misplaced” anyone; a bomb displaced them all. Still, the result was mostly the same: generations peeled away from one another, everything turned to radiation and dust. In one particularly troubling passage, Hersey describes the experiences of the children of the Nakamura family who, “in spite of being very sick, were interested in everything that happened.” Not only were they interested, Hersey explains, but they were “delighted when one of the city’s gas-storage tanks went up in a tremendous burst of flame.” Once more, I am left thinking about scale, about perspective, and about what a bomb means to a boy 68 years removed from the bomb itself. For H., the cover photo of the mushroom cloud was not a bomb, but the cover of a book. It didn’t matter what that book was about. For him, a book was a book, not a bomb, and books--he knew--never harmed anyone. Generally. But how might one diffuse a book if one had to? If the material was simply too painful to read? I admit it: Hersey’s book is indeed painful to read, but I wouldn’t want to diffuse it. By book’s end, I figure I’m left hurting the way Hersey wants me to hurt—not by drama or sensationalized writing, but a weapon far crueler: factual reporting on the lives of those who were spared. Of course, when it comes to Hiroshima, I’m not sure anyone was spared. Some people simply survived. Next time, Friend, I swear to you I’ll read something lighter. How could I not after this? Until then,

1 Comment

J. Pfeiffer

5/8/2014 11:23:11 pm

I've read this post a couple of times, and I have, finally, something to say about it. It is the fact, that at the end of WWII, we as a nation decided that the war we were fighting was so horrible, so terrible, was so desperately unwinnable, that we had to kill the enemy's innocent citizens - men, women, and children, to make it stop. Now we have to carry that damning knowledge on with us forever as we continue to be Americans. It is part of us, and I don't exclude any of us from our own small responsibility for the horrors wrought by our nation to continue to be our nation.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorB.J. Hollars is a writer and a teacher. Archives

June 2014

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed