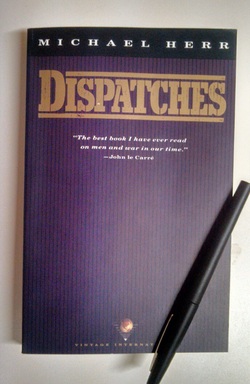

Dear Friend, I just spent the day with Michael Herr’s Dispatches, and let me tell you, I’m glad I don’t have to spend another. Not because the book was bad, but because it was terribly good—honest, true, and an intimate look at the Vietnam War that we somehow missed in high school history class. In fact, after finishing Herr’s book, I returned to my dusty, old textbook, cracked it for the first time in a decade, and marveled at how an entire war had been condensed into six or so pages. And none of those pages contained a single name of a single soldier: just politicians and death counts. Herr’s book is not about politicians or death counts; it’s about the casualties of war that kept on living. It’s a pastiche of soldier life told from the occasionally high, occasionally drunk reporter who embedded himself alongside them. Yet it's Herr’s close proximity to his subjects that creates such an unrelenting read. It’s the kind of book you absorb with your mouth hanging wide, wondering how it could ever be true. But beyond the individual anecdotes (can stories this cruel be called “anecdotes?”) lie the seeds of philosophical inquiry. We can’t help but ask the big questions when reading about soldiers who gobbled drugs to keep from asking them themselves. I can't say I blame them. What good were the “big questions,” after all, for men who were trained not to question? Momentarily inhabiting the mindsets of the soldiers, Herr comments on these questions: “No fair was no good,” he writes, “Why me? The saddest question in the world.” For Herr, finding causality in the chaos was a fool’s errand. He writes: “You could make all the ritual moves, carry your lucky piece, wear your magic jungle hat, kiss your thumb knuckle smooth as stones under running water, the Inscrutable Immutable was still out there…” Translation: their deaths were always awaiting them, regardless of who they appeased with what. While war movies often depict the victors collecting relics from their dead, I’d never considered the motivation of the action. Yet Herr reveals it, describing the act as “a little transfer of power…” It’s chilling, Friend, don’t you think? How easily a victim can be transformed into a talisman, something to be collected in the hopes of protecting the one who did the killing. Most of what I know of war I’ve learned from my grandfather, who—like so many veterans—preferred not to speak of it during his lifetime. He left no war talismans behind, just an audiotape, one I’ve listened to again and again in an attempt to understand the part of him I never knew. Growing up, sometimes I’d stare at that wobbly-kneed man and wonder How was he ever a soldier? I was young, and still lacked the imagination to understand that beneath his current exterior was an earlier version, and beneath that one, another. Yet even on the tape, my grandfather seemed to spare listeners the worst of it. The way he spoke of war, you’d think it was all guarding bridges and stirring to the sound of young French girls singing the soldiers awake. There are only a few minutes on that 60 minute reel in which he delves into the darkness, briefly touching on the time he killed the German soldier (who happened to already be dead), and the time he remained on high alert as enemy soldiers crept closer and closer throughout the night. The second story is my favorite, the one in which my grandfather—just a boy then—clutched his gun tight as a thump, thump sound startled him every half an hour or so, making sleep impossible. He remained on a hair-trigger throughout the night, only to learn at sun-up that the sounds were not coming from “enemy soldiers” but from some nearby apple trees that happened to be shedding their fruit. He called it "The War of the Apple Trees," and dedicated so much time to the tale it made me wonder if fighting apples was the most action he ever saw. But as I later learned, he fought many battles beyond the apple trees, even earning himself a few medals in the process. One day when he picked me up from kindergarten, I noticed a Purple Heart emblem affixed to his license plate. “What’s it mean?” I asked him. I wish I could remember what he said. All I know is that he survived when others didn’t, and that it probably wasn’t fair. Why him? Why was he so lucky? And why was I so lucky as to have benefited as a result of his luck? Lucky enough to be here today, writing to you, because the universe saw fit to spare him. Take care, Friend. Keep those talismans close. Until then,

1 Comment

J. Pfeiffer

5/6/2014 03:30:47 am

I am coming to this blog late, so my comments are not arranged chronologically. Rather, I comment in the order that I read your posts, so here is this one: You remind me in reminding yourself that the people from our past and who have lived in the past before us have a valuable, even invaluable set of experiences. We forget them to the lessening of our own self. Thanks.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorB.J. Hollars is a writer and a teacher. Archives

June 2014

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed