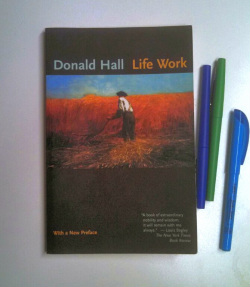

Dear Friend, Apologies for the long overdue thank you for Donald Hall’s Life Work, which I received several years back and continue to enjoy thoroughly. Perhaps “long overdue” does not do justice for my long silence, though I hope you read this silence not as a dropped frequency between friends, but as proof of the great mulling over of many things, all of which were spurred by Hall. On my most recent reading, I found myself studying the book not so much for the words within, but for my own notations from my previous encounter with it. I often date my notations—(as you know, my sentimentality knows no bounds)—though I regret that in this instance, I didn’t. And so, the book has become a time capsule without a clear start date, though I still recognize the young fool who once cluttered its pages with his notes. For proof of that fool, you need only open to the first page—the page prior to the title page—which the younger me employed as tracing paper. However, rather than trace the title in its entirety, I only bothered to trace the second word: Work. I hadn’t even made it to the first word on the first page, and already, I’d zeroed in on “work”—highlighting it not only as a reminder to myself (“Get to work, Hollars!”), but so that I might consider the word conceptually as well. Which is what Hall does for the remainder of his book, providing a kind of biography of work, a personal exploration of his ancestors and himself and the ways in which work has changed. For his own part, Hall claims—in the opening line, no less—that he’s “never worked a day” in his life, though I begin to doubt him when he makes casual mention of his pre-dawn, witching hour wake-up calls, his black coffee and mornings at the keys. I mean, that’s got to be work, right? Even for those of us who claim to love it. Not so, says Hall, and as proof, he shares an anecdote from his college reunion, one in which any number of former classmates make mention of Hall’s self-discipline. “For me…it required no discipline to spend my days writing poems and making poems,” Hall reflected. “If I loved chocolate to distraction…would you call me self-disciplined for eating a pound of Hershey’s kisses before breakfast?” Sure, I get it, but writing—under no circumstances—should ever be confused with Hershey’s Kisses. The Kisses are the reward, after all, for a good day at the keys. Don’t get me wrong; I admire Hall’s gusto for the craft. But on the other hand, I admit that some part of me just wants to see the guy break a little, want him to reveal some chink in the armor. Though I suppose what I really want is some hint of solidarity, some clue that writing is still hard, even for a guy like him. Yet by book’s end, I feel as if I’ve missed most of his toil. For Hall, it seems the problem is never finding the right word, but finding enough time in a single life to write down all the right words. Which brings us to mortality (somehow we always get back to mortality, don’t we?), and Hall’s great moment of clarity—his theory for why we work. After surviving a bout of cancer, he came to this conclusion: we work to defy death. I kind of like that. After all, how many times have we heard the phrase “Work oneself to death?”, and yet in Hall’s usage, death is not the result of the work, but the sparring partner, someone we might dodge again and again if we get the rhythm right. The other reason I appreciate the idea of “writing as defiance” is because it draws attention to our less-than flattering motives. Yes, we writers write for all kinds of magnanimous reasons (says the writer), but we also do it for more selfish ones (the writer whispers). Such as our attempt to sate our insatiable egos, or—related—fulfill our illogical dreams of fame and fortune, however silly that may seem. My motives, too, are about as pure as the Mississippi River, though I tell myself that the other reason I write—the reason I wake at my own pre-dawn witching hour and bumble down the stairs—is because the act of writing seems the most meaningful way I know to pass the time. Have I told you about the time I first created something? I’m not even sure what that something was, though if memory serves, it involved a popsicle box and a toilet paper roll. Regardless, by the time my “something” was complete, I paraded my creation around my living room the way I imagine God must have—in God’s living room—after creating the heavens and the earth. I admit, ashamedly, that for a brief instant in my fifth year of life, I felt as if I’d changed the course of human history. Be it by divine spark or unfathomable genius, I had been given the simplest of materials (see: popsicle box, toilet paper roll) and created…something! I spent much of the remainder of that afternoon peering out the window and awaiting my ticker tape parade. I regret to inform you that there was never any ticker tape parade. And even more tragic, by day's end, my mother mistook my “something” for trash and disposed of it without a second thought. She hadn't even remembered that she'd disposed of it, and by the time I dug it out of the trash, my something was well beyond repair. No, I did not require therapy to overcome my loss—(the world’s loss! I thought). Instead, I just got over it. Because it’s easy to get over things that are destroyed when there’s some new thing pressing on the horizon. As I grew older, I applied this logic to my writerly pursuits as well. One last word on Hall, because I feel as if I owe the man an apology: I didn’t mean it when I said I wanted to see him “break.” I do not want that. It’s hard enough just watching him come close. But we do watch it, near book’s end, when he writes of the struggles of growing old. He notes how “Every day is a seesaw of hope and despair” (something I know), and also “Once a day I weep…” (which I do not know). After I read this, I realized that the last thing I wanted was for him to break or be broken. I don't want that kind of solidarity if that’s the cost. What I much prefer is for him to leave me with the impression that he is--and always will be--unbreakable. That’s the kind of solidarity that serves us all. All right, enough with the prattling, I’ll turn off my faucet now. But please write soon. Let’s not let another six years slip by. Until then,

1 Comment

J. Pfeiffer

5/15/2014 11:31:39 pm

Once again, because this is the sixth or seventh response I have made to this blog, I am entertained by clarity and humor of your reports. Unfortunately for me, the work of this blog is not your first responsibility, and so I must wait each week for the new post and I may be entertained anew. Your treatment of the concept of "work" from your review and your own personal picture of it does coincide with my own. As usual, I now have a starting block to push off from your writing and my own self-discovery continues....Thanks.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorB.J. Hollars is a writer and a teacher. Archives

June 2014

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed